Originally published in Car Craft magazine, May 1976

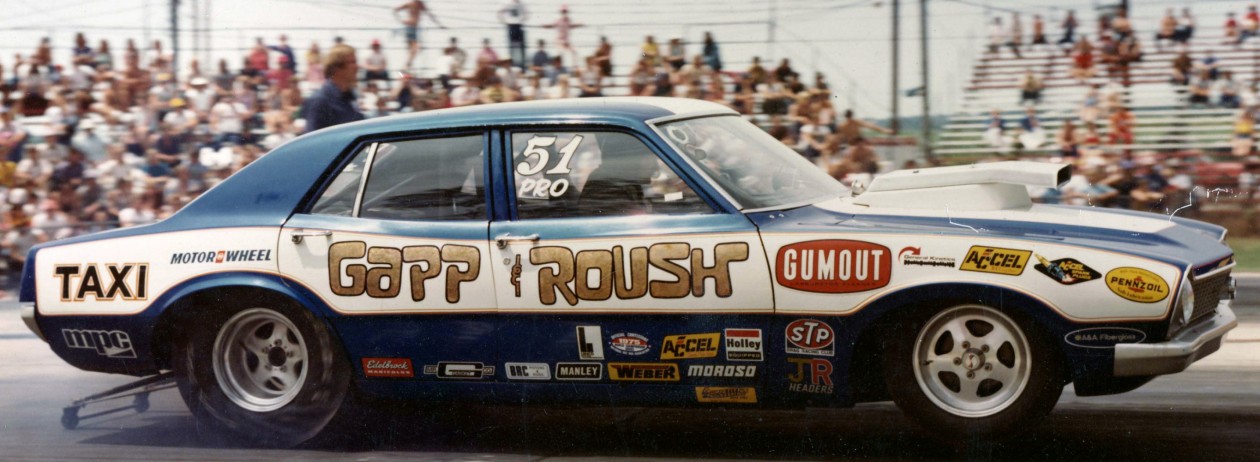

For four years now, Wayne Gapp has been brutalizing Ford rear-ends, to the delight of the photographers lining the guardrails of the nation’s drag strips. You see Wayne slalomingo ut of his water burnout and brace yourself for the crack of his dry chirpies as his Pro car bounces into the staging lights. The wall-to-wall Firestones literally melt into the pores of the pavement as the engine screams. The clutch drops, the front tires are free of the earth, and Gapp lays down another 8.80 pass.

For four years now, Wayne Gapp has been brutalizing Ford rear-ends, to the delight of the photographers lining the guardrails of the nation’s drag strips. You see Wayne slalomingo ut of his water burnout and brace yourself for the crack of his dry chirpies as his Pro car bounces into the staging lights. The wall-to-wall Firestones literally melt into the pores of the pavement as the engine screams. The clutch drops, the front tires are free of the earth, and Gapp lays down another 8.80 pass.

It’s a rare occasion when something breaks in the former World Champion’s car. An engine might let go, or a clutch cause problems,but a rearend-never. For racers who have difficulty putting together three passes in a row, Gapp’s invulnerable race cars are a marvel. Whether there is a Maverick, Mustang or Pinto body shell wrapped around the tube frame, a 9-inch Ford rearend is always charged with transmitting his Boss engine’s considerable power to the rear wheels.

Gapp and Roush’s allegiance to the Ford rearend could be dismissed as the prejudice of a pair of former Ford engineers, but the two Pro Stock stars have several convincing reasons to explain their choice. First is the Ford’s unique bearing design, which supports the pinion at both ends. All the other rearends commonly used in racing support the pinion only on its shank, so under load it “walks” away from the ring gear. This deflection is a major cause of breakage.

Secondly,the Ford rear is a Hotchkiss type, which simply means that it has a removable center section. lt is infinitely more pleasant to set up a ring and pinion with the carrier sitting on a workbench than it is to do while lying on your back under a car, as Dana 60 and Chevrolet 12-bolt owners must do. The removable center section also permits easy replacements, since the spare can be completely adjusted for backlash and pinion depth before installing it in the car.

The Ford rearend is virtually standard equipment in stock car racing, and consequently there is an enormous variety of gear ratios available. In the range most favored by drag racers, 5.83, 6.00 and 6.20 gears are all produced for Ford rearends; a Dana 60 must jump from 5.88 all the way to 6.17. In a sport where power are narrow, the flexibility in the ratio selection provided by the Ford rearend is a considerable advantage–which is why a number of GM and Chrysler racer are beginning to sport FoMoCo rearend housings.

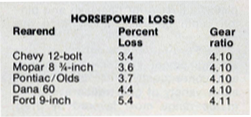

All is not sweetness and light with the Ford, however. If there is a problem with the design, it is the gears’ hypoid angle: The pinion intersects the ring gear very low. Thus the Ford rear absorbs more horsepower than other rearends commonly used as the attached chart illustrates. Roush rises to the the rearend’s defense by pointing out that the other rearends’ superiority disappears when the ring and pinion deflect, as they unquestionably do under the loads imposed in drag racing. Considering how close competition is between the top teams in Pro Stock, it’s unlikely that Gapp and Roush are going to give away any horsepower to an inefficient rearend.

Since the Ford rearends have not developed the mystique of the Dana 60, they can be obtained for very little. The 9-inch rearend was installed in almost everything that ever rolled off a Ford or Lincoln-Mercury assembly line. Thunderbirds,Galaxies, Broncos, E-200 Econolines-you name it, and it probably had a good rearend.This permits a low-budget bracket racer or street runner to shop around for a rearend with the proper width to tuck wide tires under the car. One should beware of imitations when hunting a Ford rearend, however. The 8-inch versions which generally inhabit the undercarriages of Falcons and light-duty Mustangs look very similar, but are definitely to be avoided. Take a tape measure on your expedition and check the ring gear diameter if in doubt.

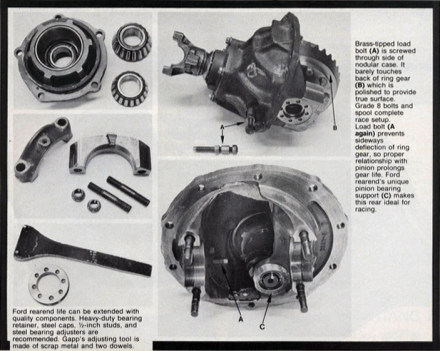

Like any part used for high performance or racing, the Ford rear has some trick pieces which increase its chances of survival. The carrier to look for is made of nodular iron, which Ford thoughtfully identified with an “N” cast in the side to aid your inspection. Gapp recommends the largest pinion bearings which Ford offers, which go under B7A-4621-A for the front, and TBAA-4621-A for the rear. The pinion retainer for these bearings is the ever-popular C3AZ-4614-B.

Setting up a Ford rearend is straight-forward procedure which is explained step-by-step in shop manuals. Remember that adding shims behind the pinion bearing retainer move the pinion away from the ring gear; in other rearends, adding shims behind the pinion has the opposite effect.

The fight against gear deflection has gone to extraordinary lengths at Gapp’s Livonia, Mich., shop. When Wayne drops the clutch and the ring gear tries to escape the rearend. Its progress is arrested by a “load bolt” inserted through the side of the third member. This brass tipped bolt bears against the back side of the of the ring gear, which is polished smooth. This bolt is adjusted so that it lightly touches the ring gear when the rearend is first set up. Under load, the pinion tries to force the ring gear away, but the load bolt prevents this sideways movement. The lessened deflection provides longer gear life and peace of mind for Gapp at the starting line.

The remainder of the racing Ford rearend is conventional. Grade 8 bolts secure the ring gear to the spool, torqured to 100 ft-lbs and doused with red Loctite for insurance. The 1/2-inch studs which hold the steel rearend caps are also tightened to 100 ft-lbs, and steel spanner nuts are used to the adjust the backlash. The outcome of all this metallic overkill is a rearend which seems totally indifferent to the abuses of 700-horsepower engines and 28 inches of racing rubber glued to the asphalt.