Editors Note: This article originally appeared in the ‘Speed and Supercar magazine, April 1973

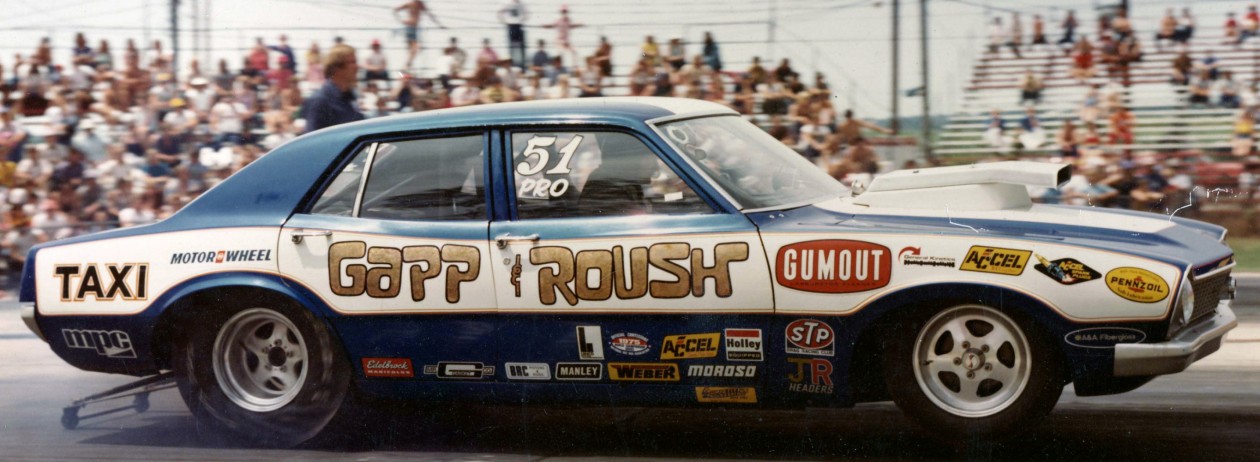

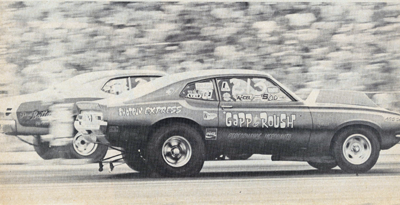

The ‘Shotgun Express’ by Wayne Gapp and Jack Roush is a ’72 Maverick with 429 power that lives up to its name

By Alex Warlordy

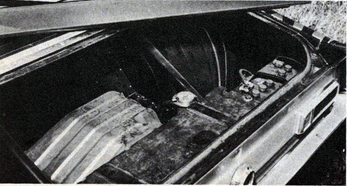

A fantastic amount of chassis work went into this machine, much of it detailed on a Bridgeport mill. For instance, the outriggers that carry the removable body are fully boxed, and tapered from the chassis on out to save weight. Welded tubes at the outer end of each outrigger provide an access path to the body retaining nuts.The goal was a 3125 pound weight with a full 55 percent resting on the rear wheels, and this is met with room to spare.

‘Glass lid over the trunk conceals an ample amount of ballast and reinforcements, designed to put a full 55 percent of the vehicle’s weight over the rear wheels.

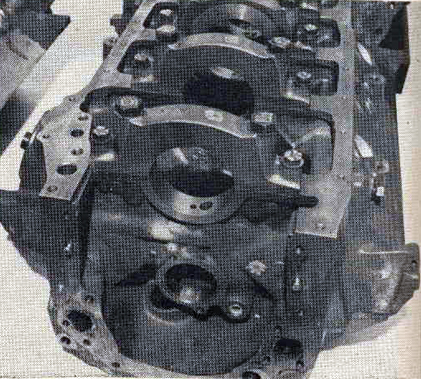

The six months work project began with Bill Jamieson and Al Buckmaster of the Gapp and Roush team stripping the entire car down to the metal and cutting out large sections front and rear. Working with chassis builder Tom Smith, they fabricated a completed new subframe of 2 x 3 chrome moly tubing with a .090 wall. This, plus a complete roll bar cage and an assortment of struts, results in a chassis that is so stiff that it will stand on three jacks as easily as on four!

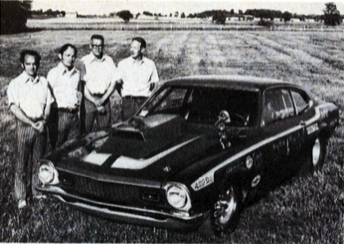

From left to right; Jack Roush, Wayne Gapp (former Ford Motor Co. engineer), Bill Jameson and Al Buckmaster built this 429 Boss into one of the fastest “Better Ideas” around today’s 1320 scene.

From left to right; Jack Roush, Wayne Gapp (former Ford Motor Co. engineer), Bill Jameson and Al Buckmaster built this 429 Boss into one of the fastest “Better Ideas” around today’s 1320 scene.

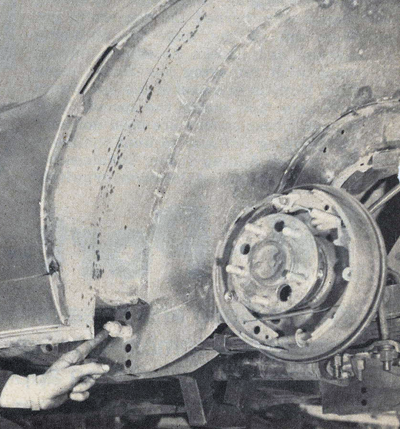

All of the original front sheet metal is gone, together with the torque boxes, replaced to good advantage by the roll cage. Another heavy section of the car that includes the rear wheel wells and the front floor area was chiseled out and discarded. To manufacture a new set of wheel wells with neatly rounded edges,the Gapp and Roush team first used a Greenlee tube benderto make up a buck of that shape.The sheet metal for the wheel wells was then formed over the tubing and welded in place for a perfect fit. Each of the aluminum panels is stiffened by an ample amount of aluminum ribbing formed by rolling it between two special little steel wheels.

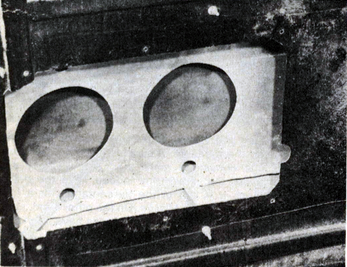

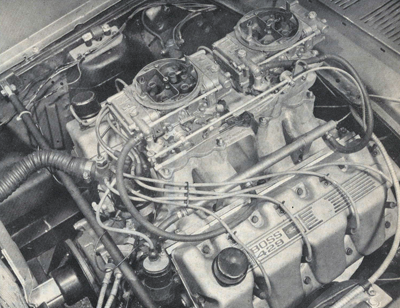

Heat shield keeps hot air from engine compartment away from carburetors.

There is nothing new about acid dipping a body or a set of doors, but Wayne Gapp figured out some neat refinements that save a lot of preparation work when the car is being painted. For instance,if the outer surface is painted, the acid will be unable to work on it, a neat trick for preserving a smooth body finish. When a door painted on the outside is dipped, the outer skin is lightened from one side only. On the other hand, acid works on both sides of the unpainted door frame, lightening it up much more than the outer shell. Naturally,all of the door regulators are gone and the original glass is replaced by plexiglas.

A stock dash board represents quite a bit of weight to be neatly air chiseled out of the car. A and A Fiberglass in Atlanta supplied the replacement dash. A few well placed cuts allowed it to be titted into the rollbar cage. Once in place, it’s glassed right back in around the tubes. While they were at it, Bill Jamieson and Al Buckmaster proceeded to fabricate a removable instrument cluster that is attached to the dash with just a few cap screws. This is handy for reworking the wiring and also made it easier to install new water temperature and oil pressure gauges. Since the original firewall is much too thin and flexible, the pedal cluster is now mounted on a cross bar under the dash board and the small Airheart master cylinder is also hidden under the dash.This way, nothing bends or yields when Wayne Gapp steps on the clutch or brakes.

Lightening up the Maverick involved some major engineering projects such as fitting it with a much lighter Pinto rack and pinion steering. It mounts up front, out of the way of the headers, on its own separate cross members. Next comes the job of snaking the steering post with two “U”joints and a section of tubing next to the engine and through the small Oilite top bushing.

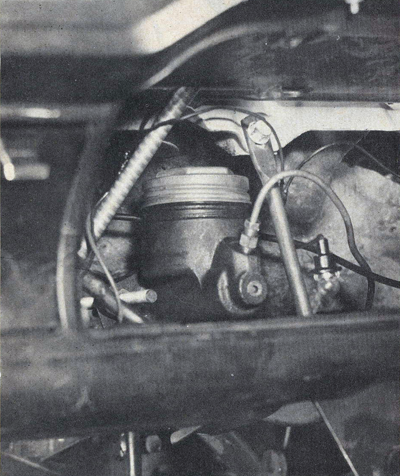

The front suspension consists of a pair of Monroe coil over shock units for which Gapp and Roush designed springs with the correct rates and heights. For the ultimate steering response, all rubber bushings in the lower control arm struts are replaced with ball joints. This firmly locates the suspension and prevents any changes in steering geometry, hence a more precise feel to the car. To add to this one piece feel, Wayne Gapp also provided a pair of tie-in bars from the chassis to the heads, as well as aluminum plates between the front of the engine and the frame. By the same token, a big welded bracket ties the battery to the right rear of the car.

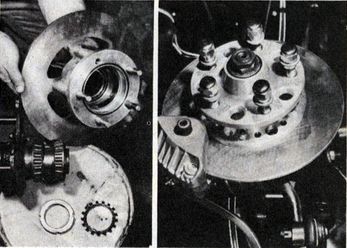

Left; Loc Performance in Livonia, Michigan, machined a remarkable set of aluminum hubs for the Airheart front disc brakes. Right; Rubber bushings in the front struts are replaced by ball sockets for more complete “road feel”.

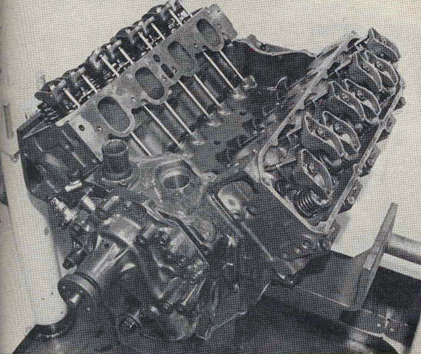

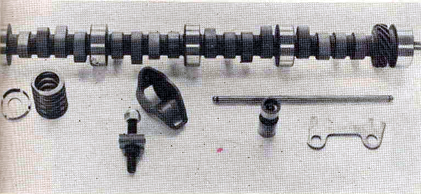

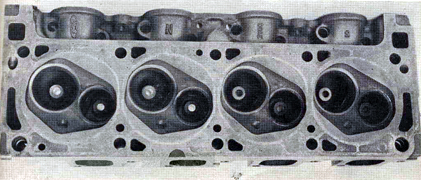

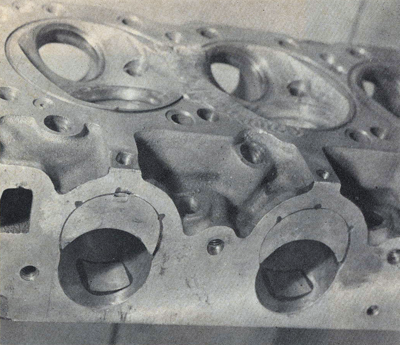

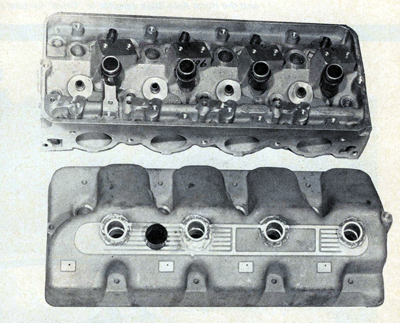

The prime purpose of the Boss 429 heads, when they were first created, was to breathe more air than the Hemis and to win on circle tracks. The drag racers were to get what was left over from the circle track program(if it wasn’t planned that way, it was certainly the end result). Later, Wayne Gapp did a substantial amount of work on the 429 heads in an effort to endow them with some of the mid-range power needed to make the drag scene. The intake ports were certainly big enough but that didn’t keep the old style head from showing a loss of two tenths. Gapp and Roush cast up some inserts that reduce the cross section of the intake ports and at the same time raise them substantially. This increases the air velocity, improves the scrubbing and mixing action, and gives the incoming fuel/air mixture a better shot at the valves. Now the fuel arrives well-dispersed into the airstream, and ready to burn efficiently. Flow is increased, despite the fact that the intake ports are smaller.

The exhaust port was raised a good quarter of an inch from the original design, improving its output by nearly 20 percent! In fact, it now flows better than the one on the single overhead cammer 427 engine. Naturally, the valve sizes have changed, but that is all that Gapp and Roush are willing to say on the subject.

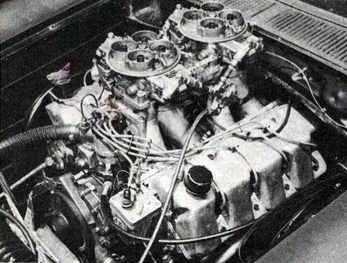

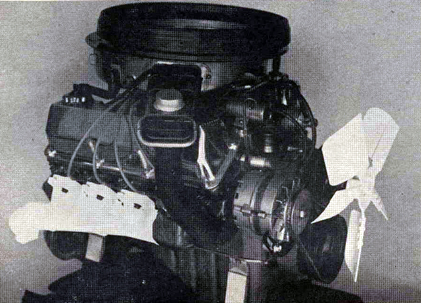

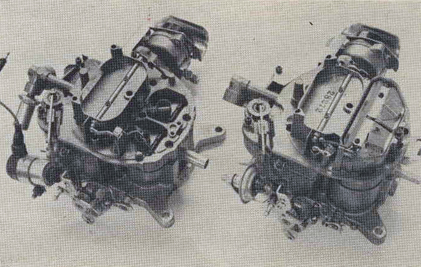

From 7000 rpm-on-up, this Monster 429 Boss seems to pull best with a set of 4500 Holleys mounted on a modest size plenum chamber, and a Weiand manifold

Manifold testing was almost as extensive as the cylinder head modification program, and you can’t very well divorce the manifold from the carburetors that sit on top of it. As Wayne Gapp explains it, individual runners are fine in theory, but even the Holley 4500 barrels are not quite big enough to feed the cylinders on a one-for-one basis for one venturi-per-port. By using a plenum chamber, or a big empty space between the intake stacks and the carburetors, you can get all of the carburetor’s barrels to contribute to each individual cylinder. Wayne Gapp adds that the Ford 429 heads flow more than the Hemis he has tested, and therefore benefit from extra intake manifold plenum size. Going a bit further, if you use the 660 Holleys which are smaller than the 4500’s, the plenum size should be increased. Latest finding is that the Boss 429 seems to pull harder in a high gear at 7000 to 8000 rpm with bigger carburetors and a small plenum.

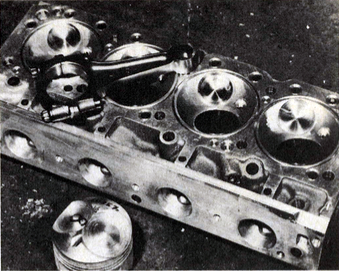

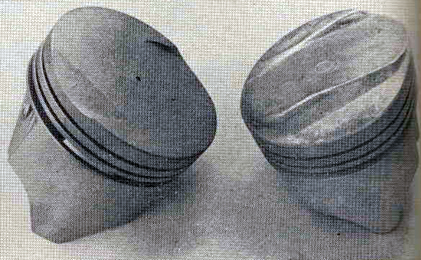

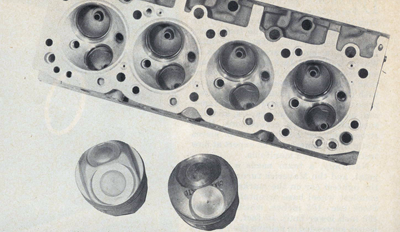

The combustion chambers have been fully machined out to a Hemi shape and the TRW pistons are made to match. Even though big steel rods are used, the pistons call for a .060-inch deck clearance. Jack Roush tells us that running a slightlysmaller .050 clearance caused the pistons to hit the chambers fairly hard, something you can ill afford with the tender and expensive aluminum heads.

The heads are machined to a full Hemi configuration and the clearance between the head and pistons is held to .060-inch

You can get an idea of the stretching forces involved from the fact that these are NASCAR rods, bigger and stronger than anything else available for the engine.The clevite 77 bearings are pinned in the rods to insure against their spinning and the crank itself is a big steel job, also used for NASCAR circle track racing.

Since the Shotgun Express is low and close to the ground, the oil pan is shallow and thin in turn called for windage tray. Baffles welded into the oil pan trap the oil and take care of the slosh on takeoff. The pickup is placed down low and at the back to insure a good supply of oil, and to exclude air. Rather than beef the oil pump and throw off an excessive amount of oil around the crank, Wayne Gapp builds his engines with the stock pump. he does, however, block of the oil supply to the the lifter galleries which gives him more oil at the bearings and cuts down on the spray inside the crankcase. Credit for all the machine work goes to Vic Vocjec of Loc Performance in Livonia, Michigan.

Well-baffled oil pan has a rear pickup fed through a trap-door; low ground clearance makes for a shallow pan

Some people are just content to pour gas in the tank and turn the key, but the Gapp and Roush team goes a bit further, like first turning the tank sideways. This way the deep sie of the tank, original designed for clearance now catches the gas rushing backwards when the car initially accelerates. Add to this a Holley electric pump, mounted at the rear, near the bottom of the tank. The fuel fill for the tank is located inside the car, away from prying hands and gas cap collectors.

Incidentally, just buying Sunoco 260 is apparently also not enough, for it doesn’t always act the same at different meets or in different parts of the country. This leads to continous work with the spark timing. At 40 degrees, the engine becomes extremely sensitive, while 38 degrees spark advance is more acceptable but may not put out as much power.

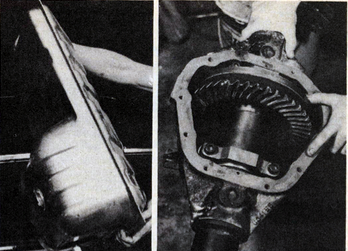

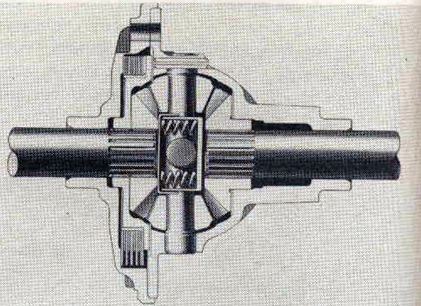

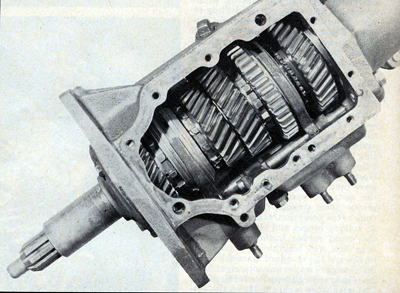

Moving down the power train, you’ll find a Ford trans with a 2.54 First gear. To speed its removal for quick clutch changes, the aluminum floor pan is retained by Dzus fasteners. A substantially narrowed Dana 60 housing was ordered from Strange Engineering. Into it went all the care and detailing learned the hard way from breakage in the previous years. For instance, the tubes are not just cut down, but are new, thicker ones with larger flanges. Full safety hubs are used, same as the ones on the funny cars. Here the hub rides on large, tapered roller bearings, as big as the carrier bearings. This way, if an axle breaks, the wheel and hub can’t come off. Strange Engineering also adapts the Kelsey Hayes disc brakes to the housing and supplies the discs.

Left; The fuel tank is turned sideways bringing the large sump section towards the rear where it “gathers” fuel when the car blasts off the line. Right: Schiefer gears are fitted to a Strange Engineering spool assembly; note the fully-machined, steel retaining caps!

Incidentally, that axle taught us an good object lesson. Some primeval racer’s instinct in Jack Roush told him to not just bolt it into the care but to first take it apart for a good cleaning, and he found that it had been shipped dry. While he was at it, Roush also proceeded to LocTite the ring bolts to the spool. The original Dana retaining caps are replaced by fully machined steel caps. When the splines in the spool proved a bit tight for the axle splines, Strange shipped a magic little bottle of acid that cured the problem in seconds.

With the near narrowed to the point where it measures just 49 inches from flange to flange, the slicks fit well within the fenders and this in turn allows the care to be lowered. That’s no mean feat with Goodyear rubber that is 14 1/2 inches wide and 32 inches tall! The 15-inch wheels just barely clear the brake calipers, which definitely limits the placement of the balancing weights.

The rear suspension went through several transformations. At first, high hopes were pinned on an intriguing set of four link traction bars, but rather than spend half a season working out the details, they were quickly replaced by “known” leaf springs and more conventional bars. As Wayne puts it, “You can’t afford to fall in love with an idea, no matter how neat it looks.” Add a set of wheelie bars, and the Maverick is ready to rear up and go. ….A hard running well respected competitor from the Ford ranks!