Here’s a promotional flyer put together by Edelbrock.

Here’s a promotional flyer put together by Edelbrock.

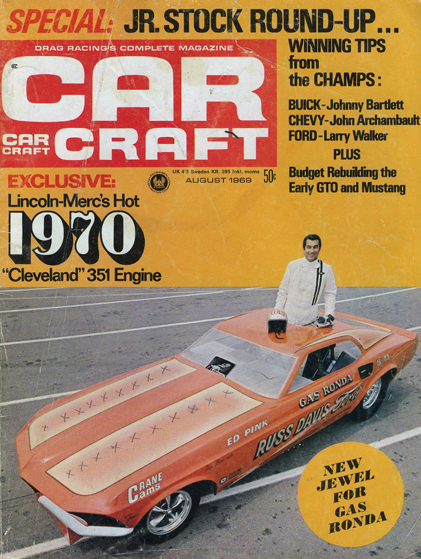

There’s quite a few tidbits in this article. What Mercury’s racing budget was going to look like. Obviously we’re seeing the beginning of the end of Ford’s racing involvement.

There’s a mention of ‘AHRA Standout Wayne Gapp’. You know that guy, right?

Lastly, the 351 Cleveland. For a variety of reason I really like this engine. My favorite part of the article is the comparison of the 351 Windsor head vs. the 351 Cleveland 2V head vs. the 351 Cleveland 4v head. BIG ports.

Here’s the cover for the magazine

The canted valve “Cleveland” head is just one feature of Lincoln-Mercury’s new entry in the middleweight muscle motor market

By John Raffa

THROUGHOUT LATE 1968 AND INTO THE EARLY SPRING OF 1969, RUMORS RAN RAMPANT IN PERFORMANCE CIRCLES concerning the future (and non-future) of Lincoln-Mercury Division’s racing efforts. One of the strongest reports had it that Mercury would drop their NASCAR racing efforts effective with the beginning of the 1970 season, meaning that the proud Merc banner would not fly at Daytona ‘7·0, and that such L-M circle track greats as Lee Roy Yarbrough and Cale Yarborough would have to seek seats behind different marques. Sadly, these rumors could not be refuted by higher-ups during a recent trip to division headquarters.

The next rumors that flowed in under the door purported that all Mercury activities in performance areas would cease for ’70; i.e., such drag racing names as Nicholson and Schartman would no longer be listed on Mercury performance brochures (which would themselves cease to exist) and that “Dyno” and “Fast Eddie” would be making new deals with other performance camps. Well, don’t you believe it! As of this writing – in early JuneMerc’s drag racing activities and plans for the new year are still very much alive, with Schartman, Nicholson and AHRA standout (and FoMoCo engineer) Wayne Gapp, still very much in the hi-per picture.

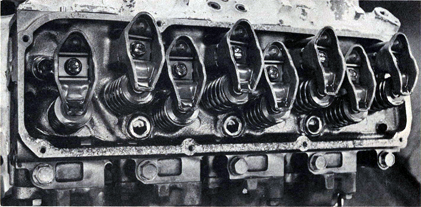

Canted valves are immediately obvious upon cracking the rocker covers. Stamped steel rockers pivot on sintered iron fulcrums of 4V head and aluminum fulcrums of the 2V.

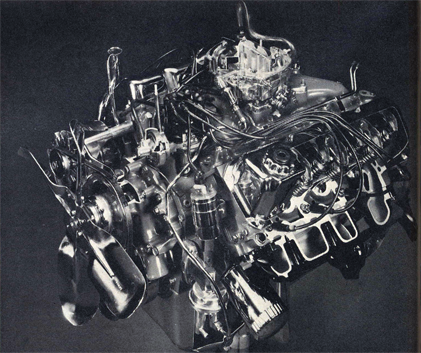

Not only is Mercury going ahead with performance plans for the drag racing world, but the racing types in Dearborn are all a-twitter about a brand new canted valve mill that will be introduced shortly after midSeptember. It.looks to be a real stormer in the growingly popular medium displacement field, and is already considerably whispered about as the “Cleveland” engine. Looking to see what all the loud whispering was about, we we were graciously admitted into L-M’s engine development labs during preproduction tests and we observed the following.

The most modern Merc mill displaces 351 inches, and before you yell, “Hey, that’s not new,” read on. Mercury personnel have a ready reply to cut short that statement. The response goes, “The 351-C is so different from last year’s model that even the spark plugs are different!” And that’s the truth. The 351-C heads (the “C” stands for their origin point, L-M’s Cleveland foundry, where the new heads are cast, and gives the name to the new “Cleveland” series) use 14mm plugs to allow use of the biggest valves possible and still retain sufficient cooling. But we’re a bit ahead of ourselves. Let’s look at the overall engine in a little detail first.

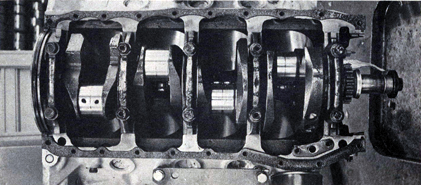

Nodular Iron crank is common to both the 2V and 4V configurations. Two bolt main design proved reliable in initial tests but can be changed to four bolt if necessary.

Immediately identifying the new open chamber design, while the 4V (4- barrel carb) head has the “advanced wedge” shape with approximately 72.5% quench area. Valve sizes for the 2V are 2.03 intake and 1.65 exhaust, while 4V readings are 2,19 and 1.71. The engineering part number on the 4V 351-C head assembly is D0AE-6049-G, while the engineering part number on the 2V head assembly is D0AE-6049-F.Another difference in the 2V and 4V heads is in the rocker arm fulcrum materials: for the 4V, they’re made from sintered iron, while those on the 2Y are of aluminum. Rockers are identical on both models, fashioned of lightweight stamped steel.

Getting back to the short block, we find that 2V and 4V models share a common crankshaft, made from nodular iron. Cranks in both t’C” engines are attached with two-bolt mains; although the block was designed so that four-bolt mains can be fitted a bit later, if needed. In testing so far, the twobolt design has shown no fatigue on the lower end of..either model, Pistons for both are cast aluminum and are holding up well in tests for either c.r. figure. They’re fastened to the connecting rods by pressed pins. Rod bearing sizes are 2 5/16 inches and the crank’s five main bearings measure 2 3/4 inches.

In the camshaft bores, the only grind tested to date are those designed to meet IMCO emission systems requirements, though we expect to have more to report from that department a little later on especially from after-market grinders within the performance industry.

Oiling for the “C” engines is similar to that found on older “385” series models, using a conventional oil pump with oil forced to the rockers through tubular pushrods. The pump body is of cast iron. Firing of the 14mm plugs, at this point in the engine’s development, is by a conventional single point, dual diaphragm Autolite unit.

Weight of the “Cleveland” engine looks to be right around 580 pounds with manifold attached, but less flywheel; and transrnissions available will be a 3-speed all-synchro model as standard, with a torque converter automatic or choice of two four-speeds (close and wide ratio) as options.

We realize that details are a little sketchy as reported here, but as we said near the start, we just got our first look and compiled the attending data some time before the “Cleveland” went into production. We were assured at that time, though, that further changes would only be in the way of refinements, the nature of which we’ll report to you at the earliest possible date. We thought you’d like to see it first in the pages of CC, anyway.

Intake, exhaust and combustion chamber view of heads, left to right, contrast 351 “Windsor” design (left) with open chambered 2V (center) and partial quench 4V (right)

Next month, we’ll be taking a long look at the L-M Division automobiles in which you’ll find the new “Cleveland” stormers, along with a complete report on all the other powerplants in the Merc line. And, of course, we’ll be tracking down all the latest rumors on Merc’s participation in the performance world for 1970. As the man said, “join us, won’t you?

From Car Craft, August of 1969.

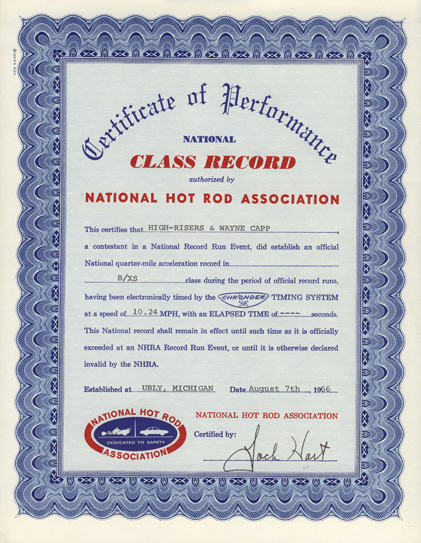

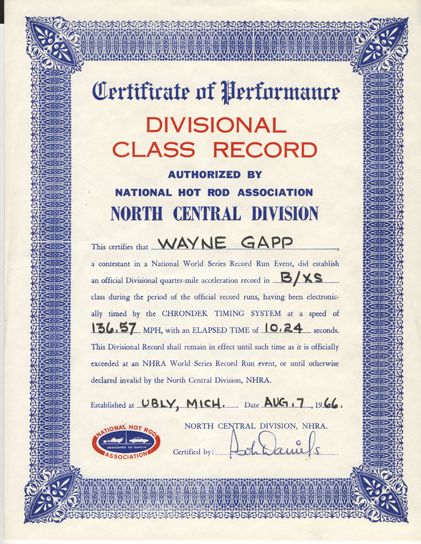

Here’s a pretty cool bit of history. A certificate of performance from the NHRA for a class record.

Both certificates are from the NHRA, one is Class and the other is Divisional.

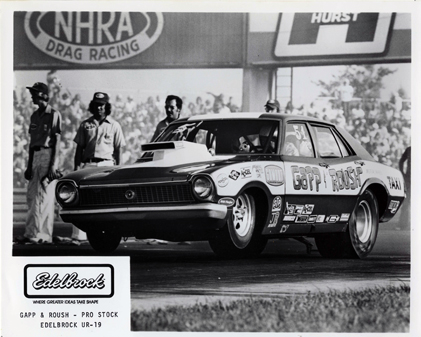

From a not-so-small shop in Livonia, Michigan, Wayne Gapp and Jack Roush apply their winning formula to make Fords fly

By Bob McClurg

Do you suppose when Ford Motor Company came out with the Boss 351 they even imagined that teams like Gapp and Roush would have the Cleveland running 8.70’s in Pro Stock? No one can argue with the success achieved by the Livonia, Michigan, Ford wizards. Their advances in racing engine development are second to none and they have one hell of an impressive track record to go with it.

You’ve seen Gapp and Roush at the races. The World Champions had themselves a pretty good year in ’73 with their Pinto, and their new Mustang II and super-controversial Maverick four-door sedan arent’ doing all that bad in the Pro Stock wars this year.

Gapp and Roush are true engineers in every sense of the word. They are thorough no-nonsense types who seem to keep coming up with new innovations to make Ford products fly. Their high-port 351 Pro Stock heads, front dry sump systems and complete racing engines and cars have made them the kingpins of Ford quarter-mile racing–and they have themselves one hell of a circle track clientele to boot.

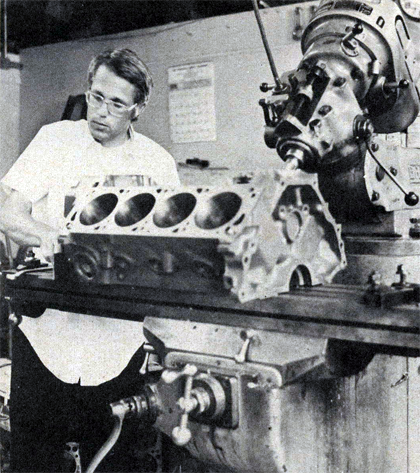

Caption: Above, the head work room,

birthplace of Gapp & Roush Hi-Port Boss 351.

Caption: Left, Ford engineer Bill Jameson

reduces the block height on a 351 to accept a set of G&R heads

Schoolcraft Road in Livonia is where the team calls home. Their shop, like their race cars, is no-nonsense. If you order a part, they either have it or they don’t. If it’s in stock, or they can get it for you, they let you know how soon you can get it right along with the price, and you can depend on what they say.

The Gapp and Roush operation proper began in early 1971, but Wayne and Jack’s involvement with engineering and racing goes back at least a decade before.

At age 35, Wayne has behind him a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Illinois and a number of years of service at Ford’s Engine Design Department. Among the many projects Gapp has worked on while at Ford are the 427 Cammer and the Boss 429 programs.

His talent as an organizer which clearly shows in the current operation stems back to the days when he and a group of fellow Ford engineers belonged to an inter-company racing group called the “Hi-Risers”. Among Gapp’s duties there was at the wheel of the club’s race car – a ’65 altered wheelbase factory cammer Comet, one of the original five made. That was in 1966. It was Wayne’s first real race car, and the machine graduated from club car to match racer, and gave the Ford Engineer much of the driving lessons which would later pay off.

The “Hi-Risers” club eventually fell apart, but continued to race. He then built a ’67 Cougar Funny Car. The injected machine was cammer powered, and alternated between gasoline and nitromethane according to the need. The Cougar made the rounds for a couple of years, and was then replaced by a Logghe-chassied ’69 Mach I Mustang powered by a injected Boss 429.

The Mustang did quite well, and mid-season was sold to Drake Viscome who was also quite successful with the car. With the sale came the decision by Wayne to return to heads-up racing.

Prior to Roush’s meeting with his partner, the 32-year-old engineer in Mathematics and Automotive Engineering worked for both Ford and Chrysler in various engineering facilities. Jack belonged to a counter racing group at Ford called the ‘Fastbacks’ and he was on a number of different projects.

Roush’s engine building talent was put to good use in prior years before the G&R alliance. Jack is plenty sharp when it comes to assembling thundering racing engines.

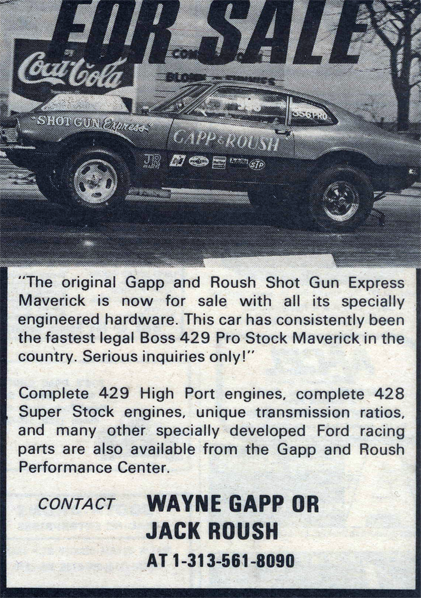

The team’s original effort was a heads up and, then legal, Pro Stock Maverick called the “Shotgun Express”. The Maverick was powered by a Boss 429, and ran consistent 9.70’s. This was at a time when the Boss motor was under much attack by everyone. Many people stated that the engine was poorly designed, the ports were too big, the heads a nightmare, etc., but Gapp and Roush took their engineering skill and made the Boss 429 run, and they are to this day the Number One authorities on the engine.

“Shotgun Express” Number 2 came about in early 1972. This car, also a Maverick, ran 9.50’s and it was one of the original Ford team cars on the United States Racing Team. But ’72 was the year of the Jenkins Invasion, and G&$ knew that the Boss 351 and the Pinto would have to be the way to go in the future. The team built a fairly mild Pinto for mainly R&D research. The car ran quite well, and taught the team a lot. In fact, it also turned out to be quite a winner at the hands of Gapp and the car’s second owner, Bob Glidden.

Tube frame cars came into necessity in ’73, and the team brought a new Wolverine-chassied Pinto to the West Coast for the NHRA Winternationals.

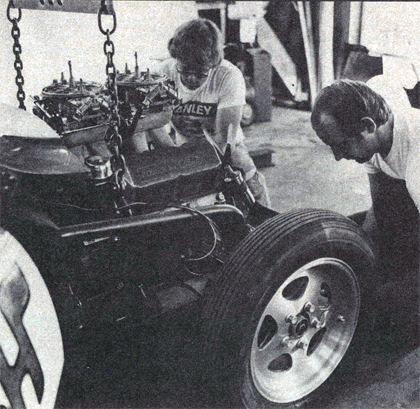

Caption: One of G&R’s Boss 351’s is lowered

into the Maverick for the Summernationals.

(ed. note: Louis Woslinski on the right)

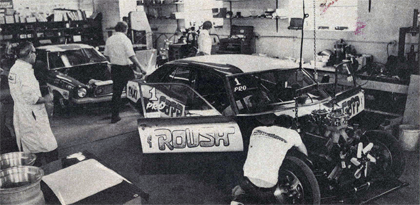

Caption: An inside look at the G&R operation.

The team cars are getting ready for a big race.

Caption: The first Mustang II, on it way to Low ET at Gainesville (9.02), and runner-up with Roush at the wheel.

Unpainted, the car ran quite well, and finished the race three weeks later fresh and in paint. The car then went to Gainesville where it set Low E.T. of the meet (9.02), and was runner-up to Nicholson. From there on it was races like the World Championships, the NHRA Supernationals, the Pop Hot Rodding Meet and a bunch more.

A trip to Gapp and Roush Performance is like stepping out of the cold into Ford Heaven. In the front lobby of the shop’s office is a Boss 429 engine on a stand left over from the earlier days. Some office conversation piece. The main office is usually occupied by Wayne’s wife, Diana, who answers the telephones, does teh billing and tries to keep a firm hand on all the fan mail and correspondence. Step into the shop itself and you are surrounded by three winning Ford race cars, more Boss 351 engines than you can shake a stick at, and whatever exotic machinery is needed to transform stock Ford into a racing piece. If you can avoid the scurry of Wayne, Jack, Louis, Ford Engineers Al Buckmaster, Bill Jameson, and three other employees, you’ll notice that the engine building room and head preparation rooms are on your right. Jack and his helpers can usually be located in this area either putting together custom engines or doing head work. Up on the walls, all around the shop, you’ll find parts, parts, and more parts. Whether they happen to be stock Ford, specialty manufactured or a piece from the G&R line, the team tries to carry every piece needed to transform that Ford into a Pro Stock, Circle Track or Modified performer. Like Wayne puts it “We try to have all the unique things that no one else carries; anything that makes a Ford engine run, we carry.”

A trip to Gapp and Roush Performance is indeed a experience. From out of engineering came a winning team, and from a winning team came a thriving business. Out of Ford Motor Company’s “Better Idea” program came the Boss 351 engine and out of the 351 came the Gapp and Roush “Better Idea”.

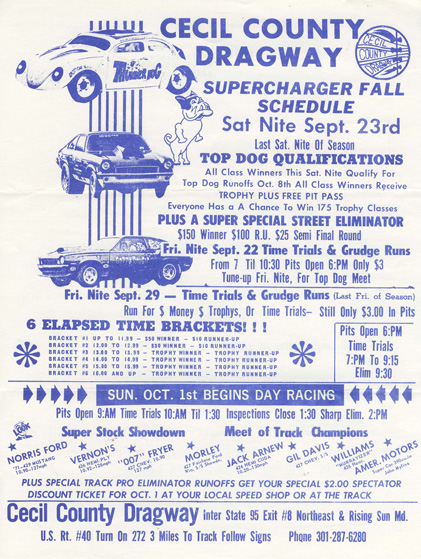

Cecil County advertising.

Interesting because of the use of the ’72 Pinto which wasn’t around long before being sold to Glidden.

Tom Bonner has taken some great pics and is posting the images and stories behind them (that’s the part I like) over at the Vintage Nitro site. Check out the site here.

It also happens that he posted another image of the Hi-Riser’s Comet Cyclone.

Check that article out here.

Head on over and wander around the site.

Well. Not really. Here’s an old ad for the first Mav.

I’ll take 2.

“…rather vicious…”

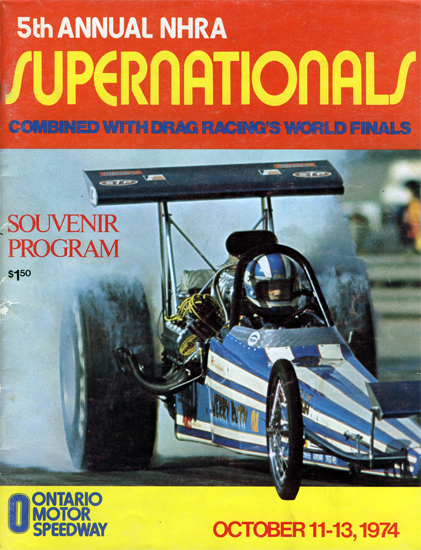

Mild-mannered in his personal demeanor but rather vicious on the race track, Wayne Gapp made some of the biggest headlines in 1974 with his controversial 4-door Maverick that took advantage of a wheelbase rule, allowing him to run 125 lbs. lighter than the competition. This advantage, coupled with the tremendous horsepower generated by Gapp & Roush-prepared engines, saw Gapp produce a tremendous record with a Grandnational-Molson victory and Summernationals runner-up along with the a new National Record of 8.84. Gapp also finished second in the Pro Point Standings at the end of the WCS season and is favored to fend off the challenge of Wally Booth’s AMC Hornet for the overall title at the Supernationals/World Finals

Nice little blurb in ‘Bits from the Pits’ in the print version of National Dragster. Yes, I’m a subscriber. Check it out here.