The following was published in ‘Cars’ magazine in 1969. I am in the process of documenting some of this stuff and am going to use this article as the ‘template’ of how I will present this information on the Web. Clearly I need to get some design chops, captions on the images would be nice as well…

It’s a fun article…enjoy.

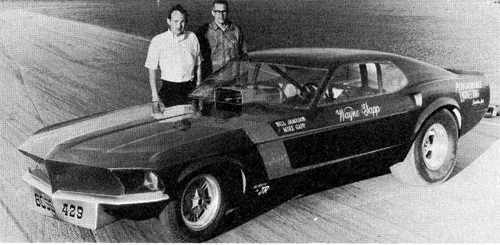

Factory engineers Wayne Gapp and Bill Jameson build an out of sight 429 AHRA-style funny.

Here’s how they went…

FROM BOSS HOSS TO BOSS GASSER

By Alex Walordy

There are only 24 hours in a day, and just a meager seven days in a week, so Wayne Gapp and Bill Jameson parcel out their time carefully. By day, they work at Ford Engineering in varying engine design functions. From Ford, it’s only a short drive to a little shop called Performance Engineering, also in Dearborn, Michigan. There they build Ford race engines. Then, of course, a man has to relax and that calls for a 429 Boss race car. Gapp and Jameson really wanted a blown fueler, but that looked like too much of a full time business in itself to be successful. Instead, they turned to a gas funny car, AHRA style.

The class rules are very strict; 430 cubic inches maximum, naturally aspirated and no less than 2000 pounds weight. End of rules! Since Gapp and Jameson are both interested in engine design and development, the freedom to make any changes they wanted fell right within their province. Also, the car stood a chance of becoming a winner without encroaching too much on their day and night schedule. The competition is fierce, with cars like Al Joniac’s Mustang, George Weiler’s Camaro, Earl Phillip’s ‘Baltimore Bandit’ and the ‘Banning Dodge Charger’ to cite a few. However, for having a brand new machine, Wayne Gapp hasn’t done badly at all. First run out, he turned 149 mph and posted a 9.2. Since then, there has been a consistent improvement in the car, as the little bugs get shaken out.

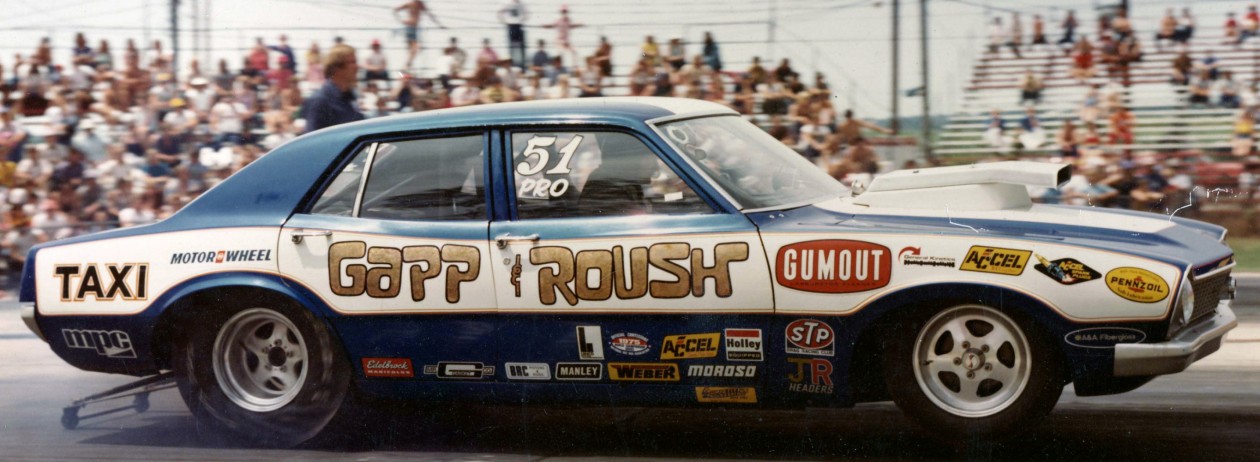

While the new Boss 429 is built strictly as an AHRA car with a 33 percent engine set back, moving the engine ahead to the 25 percent mark would make it possible to run in A/funny car under the NHRA banner. Since the current class is quite competitive and operates as a circuit, there is very little time between rounds and no chance to change engines or transmissions. In other words, to win you have to stay in running shape without breakage and the Ford pieces are turning the trick. In fact, Wayne feels that an 8.80 with a top speed of 160 is well within sight.

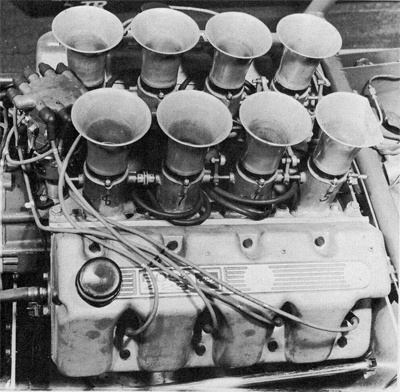

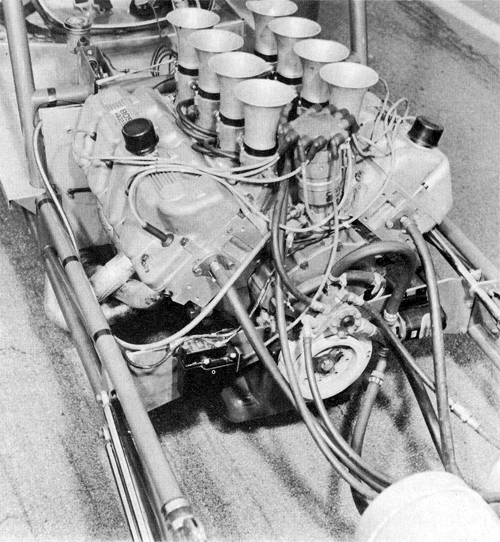

One thing about the Boss 429, it is distinguished by the biggest intake ports in the industry, and this doesn’t necessarily lend itself to high air flow velocity and great fuel distribution in a carbureted car. No matter, says Wayne, so he set up the engine to run with fuel injection at well above 7000 rpm. He leaves at 7500 rpm by dropping the hammer rather abruptly, and doesn’t allow the engine rpm to go much below 6000. In fact, Wayne and Bill Jameson couldn’t care less about what happens below 4000, since the engine never operates that slowly. End of air velocity problems.

The Boss 429 is still a brand new engine and no one was in a position to supply an off-the-shelf fuel injection unit for it. However, there must be a benefit to having a pair of engineers on the job, for they promptly designed their own unit. Eight runners similar to those of the SOHC were cast, after which side and bottom plates were fabricated out of flat stock. The whole thing was shipped to Antieaux’s Welding, and heliarced, using the block and heads as a jig to keep everything in alignment. After some machining, which included rifle drilling the new manifold to accept throttle shafts and also boring the runners out for Hilborn throttle valves, the unit became ready made bolt-on assembly.

Wayne is already thinking, of course, about the next fuel injection unit that he will build, one with even more streamlined air passages. That one will consist of a series of independent intakes joined to a common base plate. It would be a lot easier to machine since all the pieces can be made individually on a jig. One advantage would be to eliminate the difficult rifle drilling of the throttle shafts. A fuel pump drive for the Boss 429 was just as unavailable as the injector manifold, so Wayne made up an aluminum cover which replaces the stock water pump and supports the Hilborn pump instead. A hex head mounted on the timing gear powers the Hilborn pump.

Pointing the nozzles upward against the air stream instead of twoard the valve imporoved the fuel break up, and also allowed more time for the fule to mix with the incoming air. Add to this a set of intake stacks designed to produce just 14 inches of tuned ram length from the valve to the top of the intake. This, plus a set of big 2 1/4-inch diameter header pipes which Bee Line engineering trimmed to a 30-inch length, tune the engine for peak rpm. Then, to fill in the upper end of the midrange and help the car leave harder, there is a seven-inch transition to a collector. Wayne is currently experimenting with optional collector lengths of different designs to see which one puts out the most usable power.

The 429 valve train is built for the steady grind on circle tracks, 500 miles at a clip and is to sturdy and to heavy for straight drag racing. Gapp was able to remove 100 grams at a clip by switching to think wall push rods, aluminum retainers, and thoroughly reworked rocker arms. Any excess material which didn’t add to the rocker’s load bearing capacity was ground off, and this includes a small area around the oil squirt hole. The standard valve latch adjusting screw and its lock nut look big enough for double warranty life on a Mack truck. Wayne Gapp go a hold of some raw rocker arm forgings and machined them for a light-weight 3/8-inch Chrysler adjusting screw. These lightening changes plus the stock tubular valves, and a special cam, brought the rpm limit up to 8000. Quite an achievement considering the kingsized intake valves.

To raise the compression, most people are content to cut the cylinder heads, and it probably works well enough in most engines except the Boss 429. As Gapp points out, there are four “O” rings for the cylinders, and nothing less than 21 “O” rings to seal off the various water passages. Any time you cut the head, all of the “O” ring grooves must be reworked since the Boss 429 is for all practical purposes a dry deck engine. Besides, the combustion chamber has two side sections taken out of the circle so the cutting of the head doesn’t remove as many cc’s as cutting the deck of the cylinder block, where the volume gain is based on full circle area. It is, therefore, no surprise that the heads are left alone, and that decking just .025 inches from the block deck raised the compresson to a comfortable 13-to-1.

Grand National rods may be heavier than the ones made for streeet use, but they’re also designed to go 500 full throttle miles, and at a quarter mile a shot, that makes for quite a few runs. Since they’re made of 4340 steel and fitted with half inch bolts, you can understand why they last. The 429 rod bearings are .860 inches wide, while the ones on the 427 SOHC only measured .740 inches across. At first glance an eighth of an inch may not look like much of a change, but it represents a 17-percent increase in bearing area, more than enough to guarantee good life. The two partners had quite a session using clay to check the piston to cylinder head clearance and then doing a little file work here and there to work out the close spots.

The stock oil pan was deepened two inches and fitted with bustles on each side. This brough the capacity up to ten quarts, including the filter, without cutting to far in on the ground clearance. The neat street type engine oil pan baffle was left unchanged, but the sump pick-up was dropped closer to the new bottom. Moving up from there, you’ll find a race-type two-gear pump selected for its ability to digest metal particles. This pump, incidentally, is different from the more convential Gerotor pump released on the Cobra Jets and Super Cobra Jets. As an added precaution, the pressure relief spring was shimmed to increase the oil pressure.

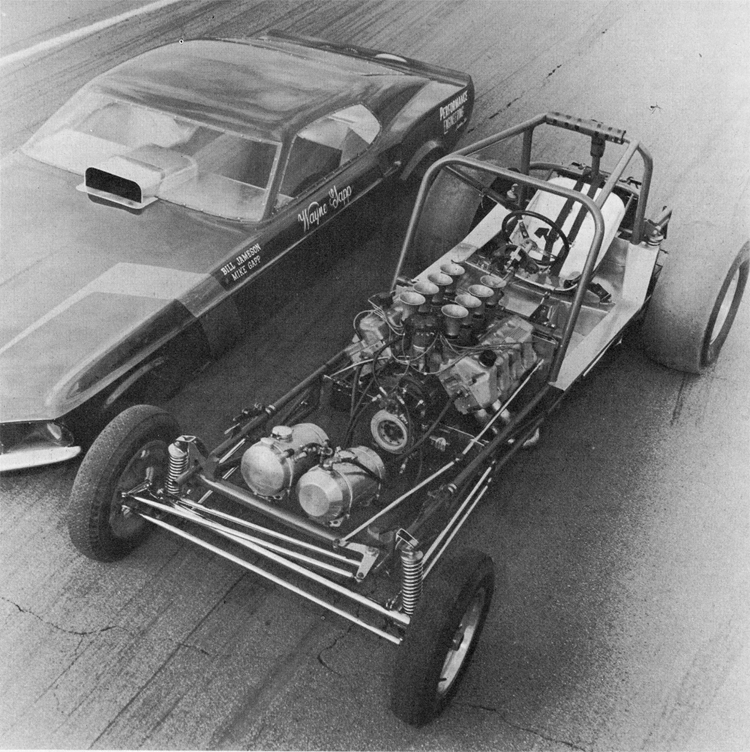

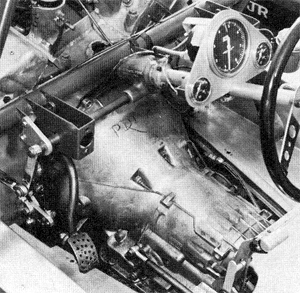

As far as Wayne Gapp is concerned, the name of the game is getting out of the gate, and there isn’t enough power available on gasoline to turn that trick with a torque converter. Instead Wayne and Bill Jameson fell back to an old stand-by, a dual disc 427 drag racing clutch, complete with a 40-pound flywheel, which they had salvaged out of their old ’66 AFX Comet. It worked then and it still does now. Now, a clutch may be great, but both Wayne and Bill are still sold on the fast consistent shifts of an automatic. However, adapting the C-6 automatic to the 429 engine proved to be something of a problem because, for one thing, the starter had to be moved to clear the flywheel. Then, some of the bolt holes and dowels no longer fit. Now, both the engine and the transmission are fastened to the quarter-inch supporting bulkhead. Helicoils (small coiled steel wire inserts) were threaded into the bulkhead so that frequent disassembly wouldn’t strip the aluminum. Three of the original bolts go straight through from the transmission to the engine while the rest tie in via the adapter. The C-6 has been thoroughly reworked to beef it up and also convert it to a full manual shift. Topping all of this is a logghe ratchet-type shifter. A 14 5/8-inch drive shaft will never win any prizes for length and even this space had to be carved out the hard way by converting the trans to use a short tail shaft. A brand new cross member, retained by just two bolts, cuts down on the amount of work it takes to remove the transmission.

Since Wayne’s machine is not straining at 150 mph, even with 4.57 gears, you can see that the engine’s rpm capability is not neglected. Logghe supplied the narrowed rear, the shortened axles and teh set of drum brakes out of a 1968 Fairlane station wagon. The drums proved more than adequate in stopping the car, have less drag than discs and also offer a good holding power on the starting line when preloading the clutch. Rubber includes a set of 12.00 x 16 M7H’s mounted on 10-inch Cragars and, so far, the best tire pressures have been between six and eight pounds. To cut down on rolling resistance up front, Wayne picked a set of radial ply 5.60 x 15 Pirellis mounted on four-inch Halibrand rims and pumped up to rock hardness.

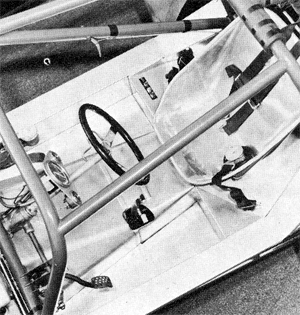

Wayne and Bill operate on a tight budget, and instead of going all out for a brand new frame they picked up a used Logghe frame in good running shape from a well-known Ford racer. It offers 120-inch wheel base, plenty of stability and ample room for the big engine set-back–it’s nice to play the percentages but you still need a certain amount of inches to accomodate the driver.

Everyone is entitled to their little secret and Wayne has been doing a lot of experimenting with frame wedging and suspension units to get the most powerful gate job. After campaigning what amounted to a wheelie machine for a couple of years, Wayne now feels that picking up the front end too much just hurts the et. “You want to go forward, not up” Mind you he doesn’t mind carrying the front wheels and putting most of the load on the rear ones, but he still wants to handle well and goin in a straight line.The wheelie casters have been brought down close to the ground and steadided with a cross-piece. This gains quick contact with the ground as soon as the nose begins to lift, and avoids the sudden changes in loading. For instance, if the front end rears up hard enough, it can then jerk the rear wheels off the ground as well, while limiting the rise gains top traction.

Right now the Boss Mustang is around 70 pounds over its 2000-pound liit, but since 780 lbs of the weight is taken up by the engine and flywheel alone, there isn’t too much more lightening that can be done. One step in the right direction was to use a lightweight 125-pound Shedlik body out of Shedlik Engineering in Inkster, Michigan.

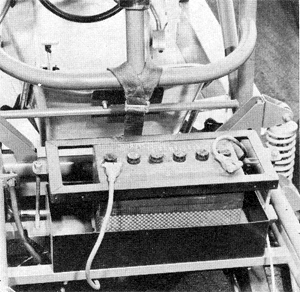

Also, Tom Smith of Wolverine Diesel contributed some very light aluminum work with cleverly formed cut-outs that are flanged over to retain stiffness while doing away with extra metal. A thirty-pound battery, complete supporting brackets will be eliminated from the rear of the car as soon as Wayne converts to an outside 24-volt battery for starting purposes. Neither partner is very happy with that because when you travel alone to a strip, that outside battery can be a nuisance. Wayne and Bill are even less happy with the prospect of chucking the cooling system, especially since a gasser usually runs hotter than the fuelers they have had in the past.

Of course, we left the best for last, an unreal paint job by Paul Shedlik, complete with a wild Cobra baring his fangs from the tail end of Gapp’s machine. In a tight race, when the competition is in hot pursuit, that Cobra has been known to hiss, breathe fire, turn on the steam and flat streak through the lights.