Bought a few negatives here and there and came across this shot.

The color in the image is great and the shot shows the details of the car.

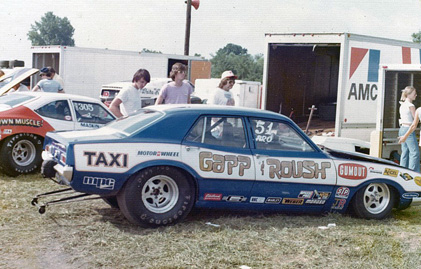

Bought a few negatives here and there and came across this shot.

The color in the image is great and the shot shows the details of the car.

Been some time since I’ve put up a shot of the 1973 Pinto.

That’s WG center left.

The NHRA posted this as the photo of the week!

Pretty cool of them to do that.

Too bad they don’t have a picture from 1975 when WG won the event.

This is NHRA’s recap of the 1975 event here.

I can help with a picture.

FYI. If I were to nitpick the picture that NHRA selected is from 1976. See here for a list of cars and paint schemes by year.

One of my favorite racing related items…period. I have one of these that is badly beat up. One of my Mom’s friend had this one and gave it me.

This one comes from Daryl Huffman who did the restoration of the ‘Gate Job’ Comet.

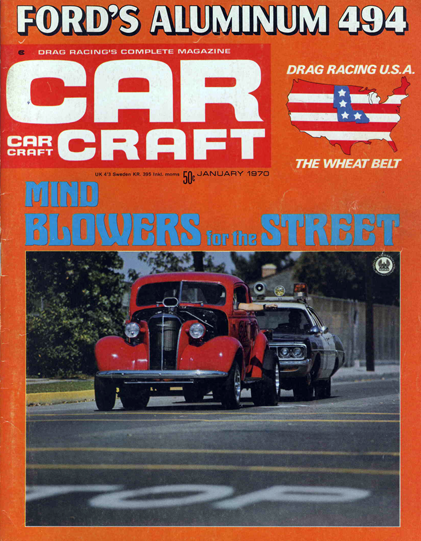

I decided I would get a few articles from the time period that talk about the Boss 429 and the 351 Cleveland. They are interesting reads especially when compared with what is said today. Check out this one from the January 1970 edition of “Car Craft”

Page 36 | CAR CRAFT | JANUARY 1970

Ford’s Boss 429, Blue Crescent, Shotgun Motor, Twisted Hemi, call it what you like. Many people are calling it a stone. Going in we decided to discard all the poor reports we had received on the Boss 429 engine and try to approach it from a fair and impartial standpoint, to give the engine, and Ford, an even chance.

In the following pages we have evaluated the Boss 429 from four different standpoints: as a totally stock “out of the box” showroom new product; as a slightly modified street and strip dual purpose performer; in several all-out fully drag strip-prepared cars; and, finally, on Crane Engineering’s dynamometer. In addition, for your edification, we are including the big inch aluminum block offshoot of the Boss 429, the 494. After conducting the four-pronged test we have concluded, as have others, that the Boss 429 engine fails in its present form when applied to the street performance situation. While the engine may be dominating the NASCAR Grand National Stock Car circuit down south, it seems to lack when tested on the drag strip. Although an industrious few – like Dave Lyall, Wayne Gapp, and the guys at Foulger Ford – have made semi-respectable showings with the engine, the Boss 429, to date, is a loser in the drag car bailiwick. The purpose of the text that follows is to tell you the reasons the Boss 429 has fared and failed, and to suggest how the situation, which is a lot bigger than the Boss 429, might be alleviated.

The answer, lies in Ford Motor Company’s approach to the whole performance car market.

Originally, the Boss 429 was developed with NASCAR (Grand National Stock Car) racing as the primary application, but as with the SOHC Ford engine, a secondary outlet for the equipment was found in drag racing. In order to legalize the Boss 429 engine for NASCAR use, 500 of the engines had to be built and offered in an available car, thus the Boss 429 Mustang was born. Because the engine was designed strictly for the NASCAR circuit, it is tailored to operate at high rpm’s. This fact can be quickly verified by checking the size of the intake and exhaust ports. They are enormous, and are generally inefficient’ at low rpm ranges.

As is common with many of Detroit’s “crash” programs, the 429 design engineers had a very limited time (in this instance only three months) to transform their NASCAR Stocker engine to a street performance car package. Although the engine was not originally designed or intended for street use, the engineers waded into the job. During the transformation from race engine to street motor, certain compromises had to be made for production and warranty reasons. For example, a single four-barrel 735 cfm carb was chosen, which is street-able, but not exactly a performance induction system for an engine of this size. Also, a massive weight valve train

was used in the street version of the Boss, which, together with the 1969 hydraulic camshaft, resulted in a performance peak of 5400 rpm. Anything close to the 5500 rpm from the engine was inviting valve float. Remember that the engine was primarily designed for high rpm operation, but because of the cost of the lightweight valves was prohibitive for production use, heavy valves were used and thus the street engine was not capable of the needed high rpm’s and another inherent problem was created. Although Ford put a 370 horsepower figure on the street version of the Boss 429 engine, the NHRA re-factored it to SS/D, which didn’t help Ford’s chances at the drags.

But the key to all of Ford’s problems with the performance cars and the thing that really put the blocks to the Boss 429 Mustang was that corporation’s Product Acceptability Standard (P.A.S.). The edict handed down from the higher-ups at Ford says that any car made and sold by the company must start when the engine is hot, start in cold weather, idle, run in traffic in fourth gear, and run smoothly at 20, 60 and 80 mph, just like a Lincoln Continental. In addition, the P.A.S. demands that the engine compartment, passenger compartment, and overall noise levels must not exceed a certain maximum. Then there’s always the performance car’s friend, the emission regulations, which are getting tighter every year. Put it all together and you can see that the Ford engineers had to do the impossible: build a production car that starts and behaves as docile as a Thunderbird, yet runs like Wayne Gapp’s injected gas Funny car. They managed to meet the P.A.S., thus the Boss 429 doesn’t make it as a muscular performer.

In comparison, the 429’s drag strip competitors, especially Plymouth and Dodge, don’t have the rigid acceptability standards that serve to strangle performance. A Road Runner or Hemi Barracuda will idle a bit rougher and stumble a bit in fourth gear when you try to lug it around in traffic at 20 mph. However, step on the throttle of a 383 Dodge or Plymouth and you’ll blow any stock Boss 429 Mustang directly into the weeds. Even the 340 Darts and Dusters, let alone Chevy’s Z-28, may give the Boss a tough row to hoe. While the Chrysler and General Motors products do have certain standards they must live up to, they don’t choke their performance cars to the point where acceleration is drastically hampered. Until Ford Motor Compony loosens their Product Acceptability Standard for their performance cars, they will continue to take a back seat to General Motors and Chrysler Corporation in performance. The emission laws are one insurmountable obstacle, but there is no government legislation that says a Boss 429 (or Cobra Jet) must ride like a Lincoln. We want to see Ford improve their position and penetration in the Muscle Car market, but the higher-ups at Ford think a competitive car is one that can spin street tires on wet pavement. Until they start making and selling cars that can hold their own against the competition on the nation’s drag strips, Ford will miss their due shore of the performance pie.

Ford’s factory-backed drag racers haven’t tried the Boss 429 because they were (1) unable to get parts from Ford (Montgomery & Robinson), or because (2) they wanted to see someone else make it work first. Kalitta has had limited success at the toll of much parts breakage, but two Ford employees, dyno operator Dave Lyall and design engineer Waye Gapp, have made the best drag strip showings with the Boss 429 to date. Gapp has a gas injected Funny which has run a strong 9.02-152. Lyall has two cars. The first is an NHRA SS/D Mustang which has run 11.24-124, but sincy you need 10.8’s on the 11.00 class e.t. record to be competitive, Dave feels the engine should be refactored to a lower class. Lyall’s other car is a gutted 3000-pound heads-up Super Stocker with glass fenders, doors, etc. The heads-up engine has a stock strock NASCAR crank, M/T aluminum rods and 13.4:1 pistons, polished ports, a Cran or Holman & Moody flat tappete cam, lightened rockers, and home-built dual four-barrel induction system. The car has turned 10.21-134.92 which is great for a Boss 429, but hardly enough on a circuit that requires 9.8’s to win. Gapp and Lyall are both doing a commendable job of exploring the engine’s potential, but unless Ford makes the parts available and the “names” try Boss 429’s in place of their ‘cammers’ the drag strip prognosis for the Boss 429 engine is, at best, bleak

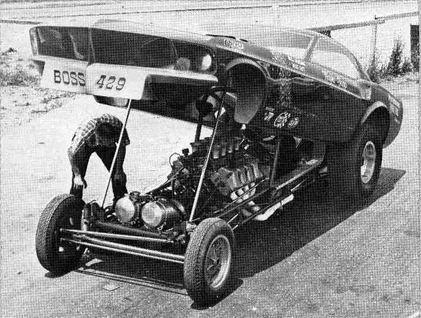

Above – Wayne Gapp’s injected gas funny has run low nines.

Below – Dave Lyall and his respectable low-ten Boss 429.

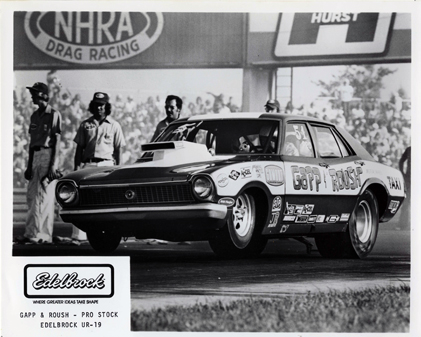

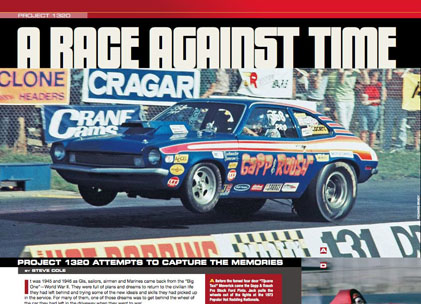

So I was perusing the Internet the other day and ran across the picture below as part of PDF file that was created for Project 1320. See that site here. They are doing some cool stuff.

They may wish to look a bit closer at the images. Here is the caption:

“Before the famed four door “Tijuana Taxi” Maverick came the Gapp & Roush Pro Stock Ford Pinto. Jack pulls the wheels out of the lights at the 1973 Popular Hot Rodding Nationals.”

Ahh..no.

The original image is large enough that:

Here is a bit of information about the NHRA Driver numbers that Gapp and Roush used. In general from 1971 to 1975 they used ‘356’ on the car when not using ‘1’ or ’51’. If they were running two events before 1975 they each used their own number ‘356’ for Roush and ‘358’ for Gapp.

After 1975 I haven’t seen a car that carried ‘356’…only ‘358’ or Dondero’s which I think was ‘1006’.

That’s because the two were operating as separate businesses and there was no need for Roush’s number.

Edit: I think this might be the Popular Hot Rodding meet held in Martin, MI

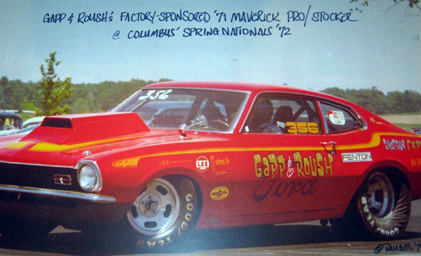

I really like this car. It’s the last Boss 429 ride. The red paint job with the striping looks great. It’s got a clean look to it and though you can’t see it in this picture it has an amazing paint job on the trunk lid. To see that go here and scroll down to the Red Maverick.

A couple of notes about this picture:

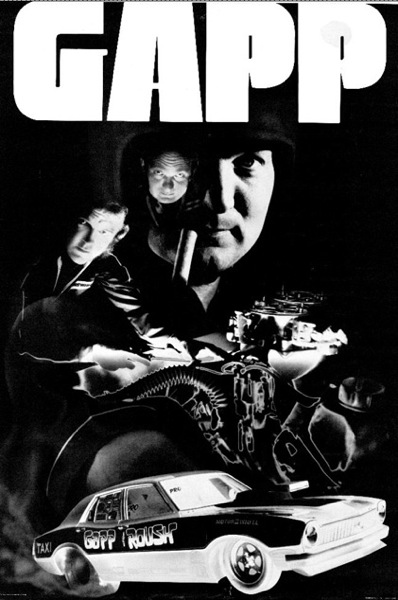

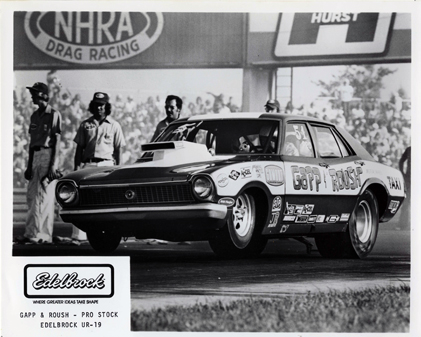

Here’s a promotional flyer put together by Edelbrock.

There’s quite a few tidbits in this article. What Mercury’s racing budget was going to look like. Obviously we’re seeing the beginning of the end of Ford’s racing involvement.

There’s a mention of ‘AHRA Standout Wayne Gapp’. You know that guy, right?

Lastly, the 351 Cleveland. For a variety of reason I really like this engine. My favorite part of the article is the comparison of the 351 Windsor head vs. the 351 Cleveland 2V head vs. the 351 Cleveland 4v head. BIG ports.

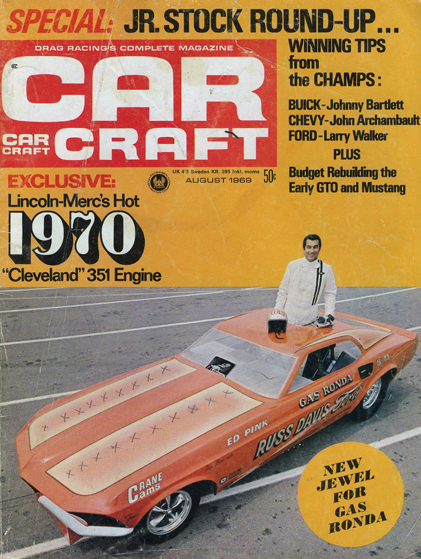

Here’s the cover for the magazine

The canted valve “Cleveland” head is just one feature of Lincoln-Mercury’s new entry in the middleweight muscle motor market

By John Raffa

THROUGHOUT LATE 1968 AND INTO THE EARLY SPRING OF 1969, RUMORS RAN RAMPANT IN PERFORMANCE CIRCLES concerning the future (and non-future) of Lincoln-Mercury Division’s racing efforts. One of the strongest reports had it that Mercury would drop their NASCAR racing efforts effective with the beginning of the 1970 season, meaning that the proud Merc banner would not fly at Daytona ‘7·0, and that such L-M circle track greats as Lee Roy Yarbrough and Cale Yarborough would have to seek seats behind different marques. Sadly, these rumors could not be refuted by higher-ups during a recent trip to division headquarters.

The next rumors that flowed in under the door purported that all Mercury activities in performance areas would cease for ’70; i.e., such drag racing names as Nicholson and Schartman would no longer be listed on Mercury performance brochures (which would themselves cease to exist) and that “Dyno” and “Fast Eddie” would be making new deals with other performance camps. Well, don’t you believe it! As of this writing – in early JuneMerc’s drag racing activities and plans for the new year are still very much alive, with Schartman, Nicholson and AHRA standout (and FoMoCo engineer) Wayne Gapp, still very much in the hi-per picture.

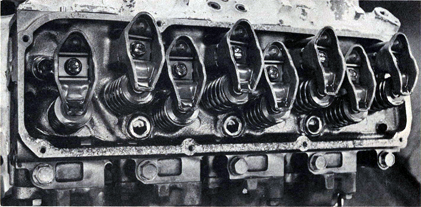

Canted valves are immediately obvious upon cracking the rocker covers. Stamped steel rockers pivot on sintered iron fulcrums of 4V head and aluminum fulcrums of the 2V.

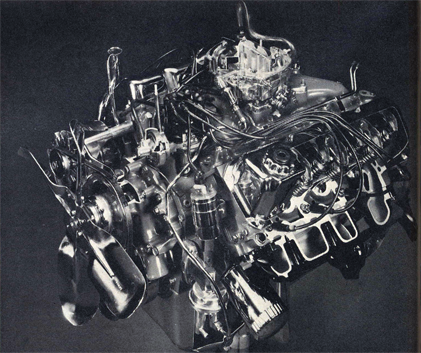

Not only is Mercury going ahead with performance plans for the drag racing world, but the racing types in Dearborn are all a-twitter about a brand new canted valve mill that will be introduced shortly after midSeptember. It.looks to be a real stormer in the growingly popular medium displacement field, and is already considerably whispered about as the “Cleveland” engine. Looking to see what all the loud whispering was about, we we were graciously admitted into L-M’s engine development labs during preproduction tests and we observed the following.

The most modern Merc mill displaces 351 inches, and before you yell, “Hey, that’s not new,” read on. Mercury personnel have a ready reply to cut short that statement. The response goes, “The 351-C is so different from last year’s model that even the spark plugs are different!” And that’s the truth. The 351-C heads (the “C” stands for their origin point, L-M’s Cleveland foundry, where the new heads are cast, and gives the name to the new “Cleveland” series) use 14mm plugs to allow use of the biggest valves possible and still retain sufficient cooling. But we’re a bit ahead of ourselves. Let’s look at the overall engine in a little detail first.

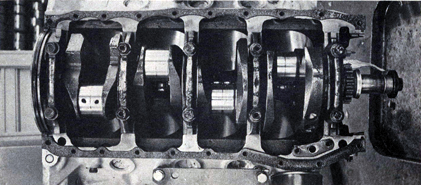

Nodular Iron crank is common to both the 2V and 4V configurations. Two bolt main design proved reliable in initial tests but can be changed to four bolt if necessary.

Immediately identifying the new open chamber design, while the 4V (4- barrel carb) head has the “advanced wedge” shape with approximately 72.5% quench area. Valve sizes for the 2V are 2.03 intake and 1.65 exhaust, while 4V readings are 2,19 and 1.71. The engineering part number on the 4V 351-C head assembly is D0AE-6049-G, while the engineering part number on the 2V head assembly is D0AE-6049-F.Another difference in the 2V and 4V heads is in the rocker arm fulcrum materials: for the 4V, they’re made from sintered iron, while those on the 2Y are of aluminum. Rockers are identical on both models, fashioned of lightweight stamped steel.

Getting back to the short block, we find that 2V and 4V models share a common crankshaft, made from nodular iron. Cranks in both t’C” engines are attached with two-bolt mains; although the block was designed so that four-bolt mains can be fitted a bit later, if needed. In testing so far, the twobolt design has shown no fatigue on the lower end of..either model, Pistons for both are cast aluminum and are holding up well in tests for either c.r. figure. They’re fastened to the connecting rods by pressed pins. Rod bearing sizes are 2 5/16 inches and the crank’s five main bearings measure 2 3/4 inches.

In the camshaft bores, the only grind tested to date are those designed to meet IMCO emission systems requirements, though we expect to have more to report from that department a little later on especially from after-market grinders within the performance industry.

Oiling for the “C” engines is similar to that found on older “385” series models, using a conventional oil pump with oil forced to the rockers through tubular pushrods. The pump body is of cast iron. Firing of the 14mm plugs, at this point in the engine’s development, is by a conventional single point, dual diaphragm Autolite unit.

Weight of the “Cleveland” engine looks to be right around 580 pounds with manifold attached, but less flywheel; and transrnissions available will be a 3-speed all-synchro model as standard, with a torque converter automatic or choice of two four-speeds (close and wide ratio) as options.

We realize that details are a little sketchy as reported here, but as we said near the start, we just got our first look and compiled the attending data some time before the “Cleveland” went into production. We were assured at that time, though, that further changes would only be in the way of refinements, the nature of which we’ll report to you at the earliest possible date. We thought you’d like to see it first in the pages of CC, anyway.

Intake, exhaust and combustion chamber view of heads, left to right, contrast 351 “Windsor” design (left) with open chambered 2V (center) and partial quench 4V (right)

Next month, we’ll be taking a long look at the L-M Division automobiles in which you’ll find the new “Cleveland” stormers, along with a complete report on all the other powerplants in the Merc line. And, of course, we’ll be tracking down all the latest rumors on Merc’s participation in the performance world for 1970. As the man said, “join us, won’t you?

From Car Craft, August of 1969.